The Future of Android, Part 1: The Legal Squeeze

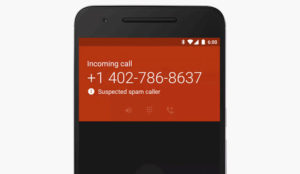

The number of attacks on Android devices has been rising over the past few months.

The malware has exotic names such as “Zitmo,” “DroidDreamLight,” “Hong Tou Tou,” “DroidKungFu,” “YZHCSMS,” “Geinimi” and “Plankton.”

In January 2010, Google removed more than 50 fake banking apps from the Android market, and in March of this year, it removed another 50 infected apps, Amit Sinha, chief technology officer at Zscaler, told LinuxInsider.

Meanwhile, Android smartphones are growing in popularity. They have extended their lead in the United States and Canadian markets, according to IDC’s worldwide mobile phone market report for Q2, 2011.

That will make for a bigger pool of targets.

“Android has the potential to become the dominant OS for smartphones,” Sinha said. “And … hackers will aggressively target Android.”

Add in Google’s support for NFC — near field communications — in Android; its launching of Google Wallet, which is undergoing field tests now; and PayPal’s using NFC on Android to make payments easier, and we could have a bit of a problem.

But that’s not all. Even if e-wallet features don’t take off, NFC has another ace in the hole — it lets owners of NFC-capable smartphone transfer documents by touching their devices together.

You can watch a YouTube video demoing that feature on the Nokia N9 smartphone here.

The implications for enterprise security are vast, especially when you recall that the increasing consumerization of IT means people are using their own mobile devices at work.

Is Google’s to blame for the increasing number of attacks on the Android OS because of Android’s design and the hands-off policy Google maintains towards the OS? Will Android survive and be made more secure? Or will Google’s laissez-faire attitude finally kill off the OS?

Google did not respond to requests for comment by press time.

Follow the Money

In September, Fortinet came across a banking Trojan it named u201cZitmo.u201d That Trojan steals one-time banking passwords. It resurfaced in July.

The mobile malware threat is expected to grow, security experts warn.

“In addition to mobile banking, many retail commerce transactions are expected to take place on mobile phones, and the cybercriminals will go where the money is,” Neil Daswani, CTO and co-founder of Dasient, told LinuxInsider.

However, we may have some time before mobile banking really becomes a major security issue.

Many banks still haven’t enabled mobile transactions on their websites, indicated Mickey Boodaei, CEO of Trusteer.

“Since online fraud is mostly a big numbers game, attacking mobile bankers is not yet a profitable fraud operation,” Boodaei remarked.

That situation will change soon. Trusteer predicts that within 12 to 24 months more than 5 percent of all Android phones, iPads and iPhones could become infected by mobile malware.

Preparing for the Mobile Malware Rush

Device makers and app developers have to shape up in preparation for the expected flood of attacks on NFC-enabled devices once mobile banking takes off.

“The NFC Forum defines the contactless protocol between devices, so much of the security is the responsibility of application providers and manufacturers,” Debbie Arnold, the forum’s director, told LinuxInsider.

The forum’s role is just to define the contactless protocol between devices, Arnold said.

Was Android Built Wrong?

The problem lies in Android’s security architecture, and the proof is that it’s easy to build applications that can get access to sensitive operating system resources such as text messages, voice, location and more, Trusteer’s Boodaei told LinuxInsider.

However, not everyone agrees this is really an issue.

“While the security architecture of Android as well as other mobile OSes can certainly be improved, just as desktop OS security has improved over the decades, the security architecture itself isn’t responsible for malware propagation,” Daswani said.

Tens of thousands of new malware binary variants are created for Windows and Mac OS, for example, Daswani pointed out. The problem of security isn’t going away any time soon, he opined.

Permissions Are a Hollow Protection

In its defense, Google has repeatedly pointed out that all downloaded apps request permission to access resources on uses’ smartphones, and users can just say no.

That isn’t enough, Boodaei contends.

Users usually just say yes because many applications request access to an “extensive list” of resources, Boodaei explained.

Google could make Android’s permissions model more fine-grained, Dasient’s Daswani suggested.

For example, when an Android app requests access to the Internet, it gets access to everything, including malicious domains and websites, Daswani said. Instead, Google should perhaps restrict an app’s access to the Internet to only what it actually needs.

“That follows the principle of least privilege, which is well-known in the security community,u201d Daswani remarked.

Google’s Slow Anti-Malware Shuffle

In addition, Google doesn’t check apps before letting their authors post them on the Android Market. Also, Google has sometimes been criticized as slow to respond to complaints about apps containing malware.

“Distributing fraudulent Android applications is trivial,” Trusteer’s Boodaei alleged. “There are no real controls around the submission process that could identify and prevent the publication of malicious applications. Compared to Apple’s App Store, the Android Market is the Wild West.”

Further, a Google Web page requesting that Google review and take down inappropriate apps from the Android Market is hard to find, Boodaei said.

The form doesn’t appear to be of much use, either, he said.

“We used it a few times with no results,” Boodaei groused. “In order to have an application on the Android Market taken down, we had to use contacts within Google who are not available to the average user.”

Google needs to make “major improvements” in its process of identifying and removing malicious apps from the Android Market, Boodaei said.

“Google already has a kill switch to remotely remove malicious apps, but this approach is reactive,” ZScaler’s Sinha stated. “They need a more proactive approach to screening and testing apps prior to allowing them on the market.”

Further, Google should control the installation of apps from other app stores such as Amazon.com because “this approach, while open-source friendly, makes the attack surface too big to protect,” Sinha said.

I have to blame Google on this one. Ubuntu and other Unix-likes have trusted sources from which to get your software. 99.9999% of all the code that the average user needs can be found in a repository that really is trusted. Those other few tidbits are riskier, but generally the risk is acceptable. In the case of Android – the "trusted source" can’t be trusted. Google needs to fix that, they need to be proactive in filtering out junk, and their reactions to mistakes needs to improve.

Android isn’t really at fault, it’s the overall administration of the apps store! I can’t praise Apple’s handling of it’s app store, but they are doing a better job at this point!