A study conducted jointly by Penn State University, Duke University and Intel Labs has found that some Android apps surreptitiously send user information to remote servers at ad networks and analytics firms.

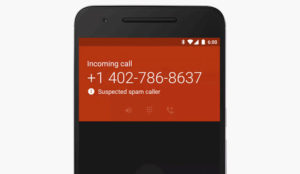

Some of the apps send users’ geographic locations to remote ad networks; others send a unique hardware identifier and, in some cases, the phone number and SIM card serial number to developers, the team stated.

By doing this, the apps appear to contravene Google’s best practices for Android app developers, which include suggestions that apps don’t send data off the server or collect unnecessary information.

Android apps tell users what information they have to access and must get the users’ explicit approval before they can be installed, Google spokesperson Jay Nancarrow told LinuxInsider.

However, that does not indicate what use the apps will make of the information they access. Could this be a problem?

Tainted Apps

The apps were discovered by researchers from Intel Labs, Penn State University and Duke University. Together, they launched a project to build tools to monitor how applications access and use privacy-sensitive data, then study and report the behavior exhibited by existing real-world apps.

The study was supported by grants from the U.S. National Science Foundation.

The researchers randomly selected 30 of the 358 most popular free apps in the Android Market that have access to both the Internet and privacy-sensitive information, such as geographic location, the smartphone’s camera and audio systems, and phone information. They built a monitoring tool they call “TaintDroid” to watch the apps while using them.

The team found that 15 of the 30 apps shared location information with remote ad network servers. Another seven shared phone identifiers with a remote Internet server.

Some apps shared location with ad severs only when displaying ads to the user, while others shared the information even when the user wasn’t running the app. In some cases, location information was shared every 30 seconds.

The researchers restricted their research to Android because “it has many features in common with other popular smartphone platforms, and because it is open source, which was necessary for us to build our TaintDroid monitoring tool,” reads a note on their site.

How TaintDroid Works

TaintDroid uses a scientific technique called “dynamic taint analysis.” This technique marks information of interest with an identifier called a “taint.” That taint, or tag, stays with the information when it is used. For example, TaintDroid can trace back the origin of the information, such as a smartphone’s GPS system, when tainted information is sent to the Internet.

Dynamic taint analysis is not new. James Newsome presented a paper on using this technique for fast automatic detection of attacks by malware in 2009, for example.

The team will make TaintDroid open source and post information on the source code on its FAQ page later. It will present its findings at the USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation in Vancouver, Canada, Oct. 6.

The team is led by Jaeyeon Jung, a research scientist at Intel Labs; and William Enck, a doctoral student at Penn State. The paper’s coauthors are Peter Gilbert and Landon Cox from Duke, Byung-Gon Chun and Anmol Sheth from Intel Labs and Patrick McDaniel from Penn State.

The Rights and Wrongs of Access

The researchers found that the Android apps they tested do ask users if they can access certain services and data, such as GPS data and the Internet, when they are installed. If the user says no, the apps can’t be installed.

That puts the apps tested in compliance with Google’s best practices for handling Android user data, which Google published on the Android developer blog back in August, Google’s Nancarrow said.

However, the best practices include telling app devs not to collect unnecessary information and not to send data off the device, and the apps tested seem to breach these guidelines.

Further, the apps don’t tell users how the data and services they access will be used.

There is no way to determine simply from the set of permissions how data will be used, and in some cases misused, the researchers claim.

That seems to contradict another section of Google’s Android app dev guidelines, which says trustworthy applications are “up-front about the data they collect and the reasons for collecting it.” A clear and concise privacy policy, with details about the type of information collected and how it’s used, “goes a long way towards generating trust and good will,” the guidelines state.

Users entrust some of their information to developers of apps on all computing platforms, Google’s Nancarrow said, when asked about the tested apps not telling users what they do with data and services they access.

“Android goes a step further than others by informing users in advance what data and resources an application may access,” Nancarrow pointed out. “We recommend best practices to further eliminate ambiguity for the user,” he added.

Openness Is a Good Thing

News that some Android apps are surreptitiously sending out user information is “very disturbing, and customers should be on their guard,” Laura DiDio, principal at ITIC, told LinuxInsider.

Concealing that information is “at the very least hoodwinking by omission,” DiDio pointed out. “The developers are telling you the truth but not the whole truth,” she explained.

“Other platforms also face this problem, but the difference here is the pervasive use and ubiquity of Android applications,” DiDio pointed out. “Gartner Group is projecting that Android will catch Symbian as the top mobile operating system by 2014,” she said.

While users of the apps tested didn’t expect them to gather the data they did and transmit it, this behavior is not necessarily malicious, Kevin Mahaffey, chief technology officer and cofounder of Lookout Mobile Security, told LinuxInsider.

“Those acts may have a legitimate reason,” Mahaffey argued. “For example, their purpose could be to serve targeted ads.”

However, Mahaffey said the results of the study are “a wakeup call for developers to make their users aware of what their applications are doing.”

Google may continue to face problems like this unless it changes its approach.

“Unlike Apple, Google doesn’t scan apps before putting them on the Android market,” Carl Howe, director, anywhere consumer research at the Yankee Group, told LinuxInsider. “That’s its schtick — the market eventually corrects, and Google always has a kill switch to handle any egregious violations. It’s certainly more of a Wild West approach.”