![]()

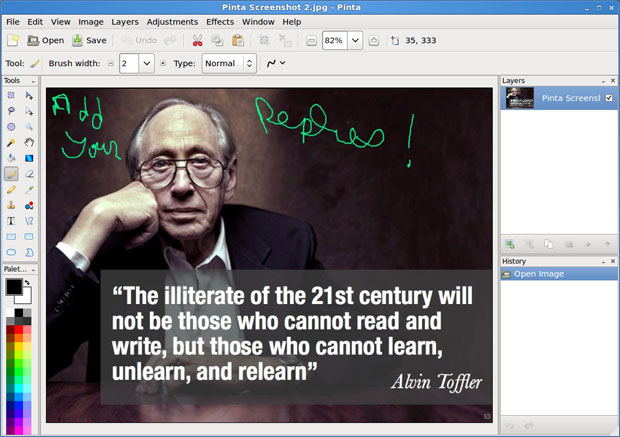

Pinta, a raster image editor, is the app equivalent of a diamond in the rough. Years of testing and reviewing open source and commercial software taught me never to assume that a relatively new application is not worthy of attention.

That lesson proved true with this youngster of an app. Development ceased on the near-infant version of this open source graphics editing app. Pinta’s creator, Jonathan Pobst, envisioned his Linux graphics application as a simple yet useful tool for drawing and editing images.

Yet its tantrum stages of development were marked by very crash-prone performances. Pobst released his last decimal version in April of 2011. With it came his announcement that it would be his last version, as he lacked the interest to pursue it.

But unlike so many other startup projects in the open source world that fizzle out quickly, Pinta did not die then and there. It survived the abandonment and is growing into a noteworthy Linux application.

Not Done Yet

Last November a new community that quickly formed around Pinta took it to the next level. The code writers stopped the crashes and tweaked its performance with a slightly expanded tool set.

Now seemingly very stable, Pinta version 1.3 is well on its way to being one of my favorite Linux painting and editing apps. For me, that is a significant event. I install and uninstall so many software packages in Linux and Windows that I tend to hang on dearly to my longtime productivity favorites.

Pinta is surprisingly useful as more than a general-purpose paint and editing tool. It is an excellent example of a simple-to-use graphics program that does not skimp on power despite its lack of a few high-end power tools. In fact, I use Pinta now for some of my regular production work.

What It Is

Pinta is a near clone of the Paint.NET architecture. Its current reiteration falls as a bridge between XPaint on the low end of this application category and GIMP on the high end.

It is a snap to use for drawing and editing images. Ideal for newcomers to this category, Pinta is also a hassle-free tool for more experienced Linux users who do not want to struggle through documentation to master a more complicated graphics tool.

Pinta is a strong example to silence Linux critics who bemoan what they claim is a lack of productivity apps in open source circles. Pinta measures up very well as an alternative to classic GIMP.

Kindred Spirits

GIMP is the de facto Linux standard bearer for image manipulation software. It is the Linux program that many experienced PhotoShop users on the Microsoft Windows platform adopt when they migrate to the Linux OS.

But it has a seemingly limitless array of tools for adjusting the image and performing countless levels of editing. That combination can make GIMP hard to learn well and confusing to use. So new users often settle for less-capable graphics apps.

They should try Pinta before reaching for those lighter-weight graphic alternatives. Familiarity with image editing and paint creation tools helps. But even without that background, Pinta is still fun and fantastic.

Cool Tools

Pinta has a feature-full environment. It includes more than 40 menu entries to adjust your images. That list crosses categories for color adjustment, photo effects, support for multiple layers, unlimited undo/redo support and common drawing tools.

I like how Pinta makes it safe and fun to fool around with a photo or other image without worrying about ruining the original. For example, not being limited to an autosave option is a life-saver. In fact, Pinta has absolutely no user preferences and setup to figure out.

Pinta displays a complete trail of your command history. That gives you one-click menu-like access to undo/redo earlier edited versions without having to hunt for a saved image and start over again.

Another plus is that Pinta caters to user whims for docking or floating icons in menus panels for tool sets within the display interface. Heck, you can even work with the tools both ways in mix-and-match fashion.

Getting It

Get the latest downloadable packages for the Ubuntu and Linux Mint distros from the developer’s website. But typical for distro package management systems, you will be stuck with version 1.0 rather than the latest 1.3 release if you download Pinta internally.

The tarball version is also available from developer’s website. That alone deserves your consideration. I always appreciate being able to get an app from the developer rather than by bouncing around software warehouse sites.

You can also get links to the required Mono libraries for the Mac OS X version and GTK+ runtimes for the Windows version from the developer’s website. Ditto for a link to the source code repository on Github.

Look and Feel

The interface Pinta uses is a likely twin of Paint.NET. But the similarity ends there. It performs much more smoothly and has its own distinctions.

If you are already familiar with GIMP, then accept that the drawing toolset you get in Pinta is hefty but scaled back. The same is true for the other tool categories as well.

As I noted earlier, I like GIMP and have used it often. Still, when I start a project with Pinta, I have yet to flee back to Gimp in search of a task I could not complete with the tools provided in Pinta.

Common but Functional

Pinta is packed with a collection of common tools carefully selected for a wide range of paint and image editing tasks. So you get Paintbrush (only not a variety of brush options). Yes, you get pencil tools, too, as well as assorted shapes, eraser and more.

Typical for a paint program, Pinta comes with straight-line and geometric primitives such as ellipse, rectangle and rounded rectangle along with gradient and bucket fill, eraser and an duplication tool called “Clone Stamp.” The remaining selection and navigation tools are typically found in this type of software.

A nice distinguishing factor that makes Pinta easier than GIMP to use is how it handles the text tools. In GIMP you find them under the toolbox palette. Here they are placed on a menu bar across the top of the working canvas. This is a very nice touch.

Another Distinction

Something else unusual in the design of Pinta is the inclusion of two tools not normally found in paint apps. Both of these features give you a new approach to working on the paint canvas.

For example, the recolor tool paints over the canvas using a hue-shift effect. The traditional method is to create new brush strokes like a paintbrush tool.

The other non-standard addition is the freeform shape tool. It draws a closed figure with a continuous solid line by automatically completing the line formed between your starting and ending points on the canvas.

This is really a cool feature because it completes the shape as you move the mouse around the paint canvas. This is similar to what another standard tool — the lasso — does. But in that case, the lasso autofills with a shaded color the enclosed shape formed with dotted lines.

More or Less

The other menu tool sets contain features typical to this type of software. But in most cases, you get fewer options than in a high-end app offering.

What you generally do not see included are tools that are less common to all but the most technically savvy users. A quick check against some of the advanced tool options in GIMP shows fewer filters and masks along with missing style controls, for example.

Perhaps the biggest example of missing tools, of sorts, is the limited number of file types that Pinta supports. It offers a basic list of the most common — even generic — file types. For example, Pinta provides seven graphic formats: Open Raster, JPEG/JPG, Tiff, TGA, PNG, ICO and BMP. Compare that to GIMP’s more than two dozen file formats.

Bottom Line

Pinta is off to a good start. It is firmly positioned in the middleweight category of paint and image editing apps. The new development community needs to expand the tool sets and maintain the app’s ease of use. That will go a long way toward growing Pinta into a heavyweight contender.

Right now, Pinta puts on a good show with an impressive yet limited functionality.